Cha Chakra: Tea Tales of Bangladesh

By Faiham Ebna Sharif

In December 2015, I went to Chandpore Tea Estate, a tea ‘plantation’/ ‘garden’ in the north-eastern district of Habiganj, Bangladesh along with a group of fellow friends among whom there were academicians, filmmakers, journalists, lawyers, political activists, and researchers; who wanted a dialogue with the Baganiyas, a community developed within their conscious who works at the tea plantations. In that plantation, the Baganiyas were protesting a government decision to set up an Economic Zone in an area, where they had been cultivating crops for over a hundred years dating back to the ‘colonial’/’imperial’ era. Then, an independent journalist, I wanted to cover the ongoing workers’ movement for land rights in that plantation owned by a multi-national corporation. However, neither the workers nor the company legally owns the piece of land. Rather, it was leased from the government for establishing the tea plantation, a customary practice in the tea industry. And within the plantation, which is also commonly known as ‘estate’ or ’garden’, it is customary as well to lease away some of the unused lands to the workers either in exchange for allocated ration or a pay cut, where they cultivate crops for their use. Interestingly, in the same year the proposed land law mentions, no agricultural land can be used for other purposes, like – building household or industrial establishments.

Once my fellow friends were going back after a day full of different activities – visiting the location, talking with different Baganiya leaders and having a discussion with the local press club members; I decided to stay back to dig deep into the issue.

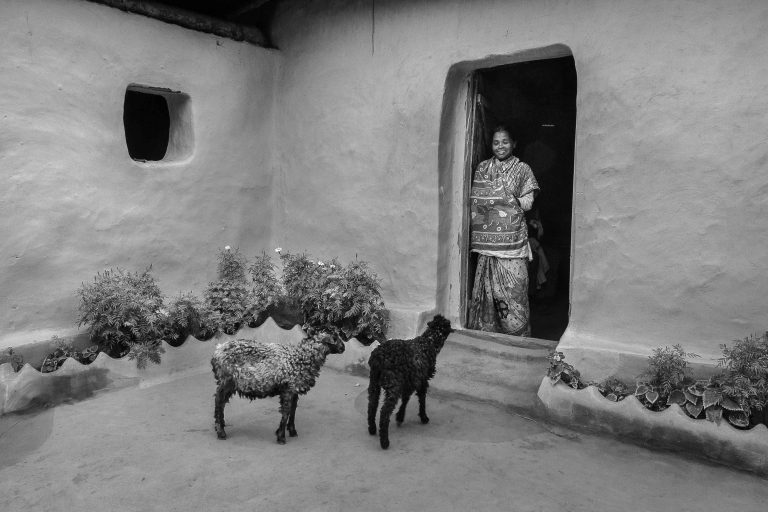

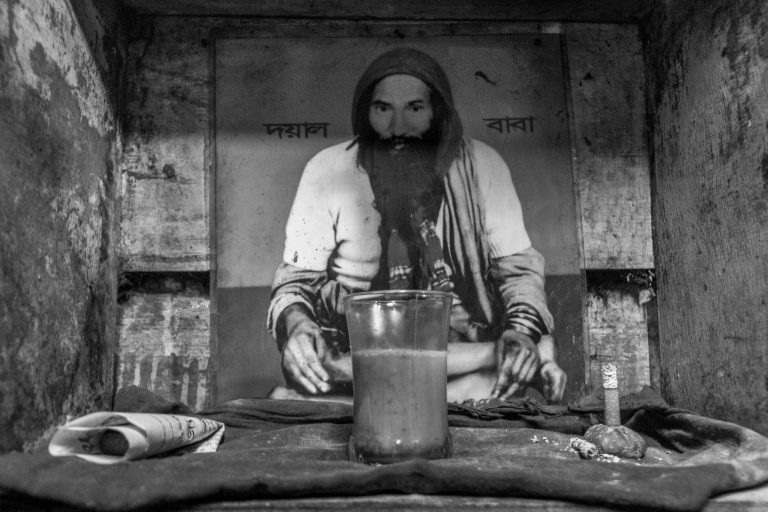

During that visit, I stayed with a Baganiya family for a few days in the labor ‘line’/ ‘colony’, a dilapidated yet beautiful village, where they live. I was moved by experiencing their ‘simple’ life, which is closely attached to their cultural practices that also consider the garden as a sacred place, which offers them livelihood. I realized, how their life is entangled with the plant and the plantation; yet the high price that the workers’ pay for our cup of tea. Being a Bengali, I grew up in a tea-drinking ‘culture’/’society’ and learned to offer a cup of tea to attend to any guest from house to roadside tea stalls to upscale cafes.

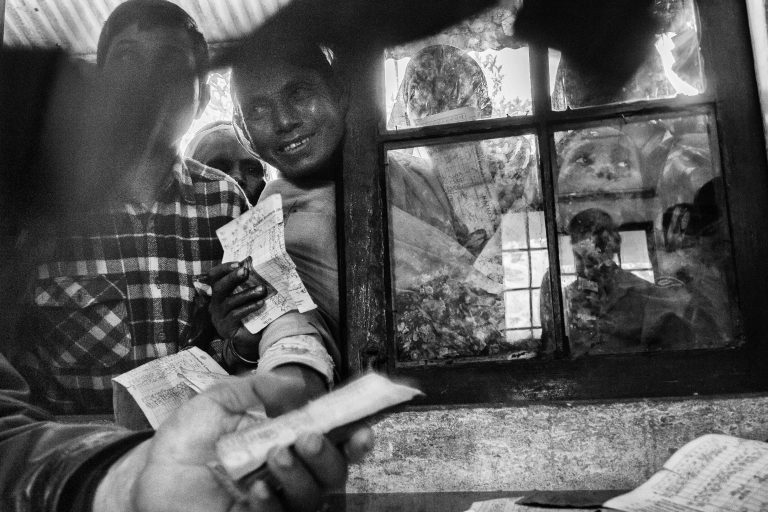

In a society, where tea is just not a drink, rather a vehicle to build up a rapport with a stranger, a medium to connect emotional and professional relationship or even the least you can offer to your guest; I was astonished to realize that the people behind the ‘drink’/ ‘product’ live a marginal life faraway from the urban center. Even today, tea gardens are one of the most popular tourist spots in the country among local and international travelers.

Usually, after a visit to the garden, one/a group must have at least a photograph amid lush green tea plants militaristically stand under the ‘shade trees’ where woman workers with different complexions, wrapped with mesmerizing colorful printed ‘Saris’ (A traditional woman wearing) are plucking tea leaves.

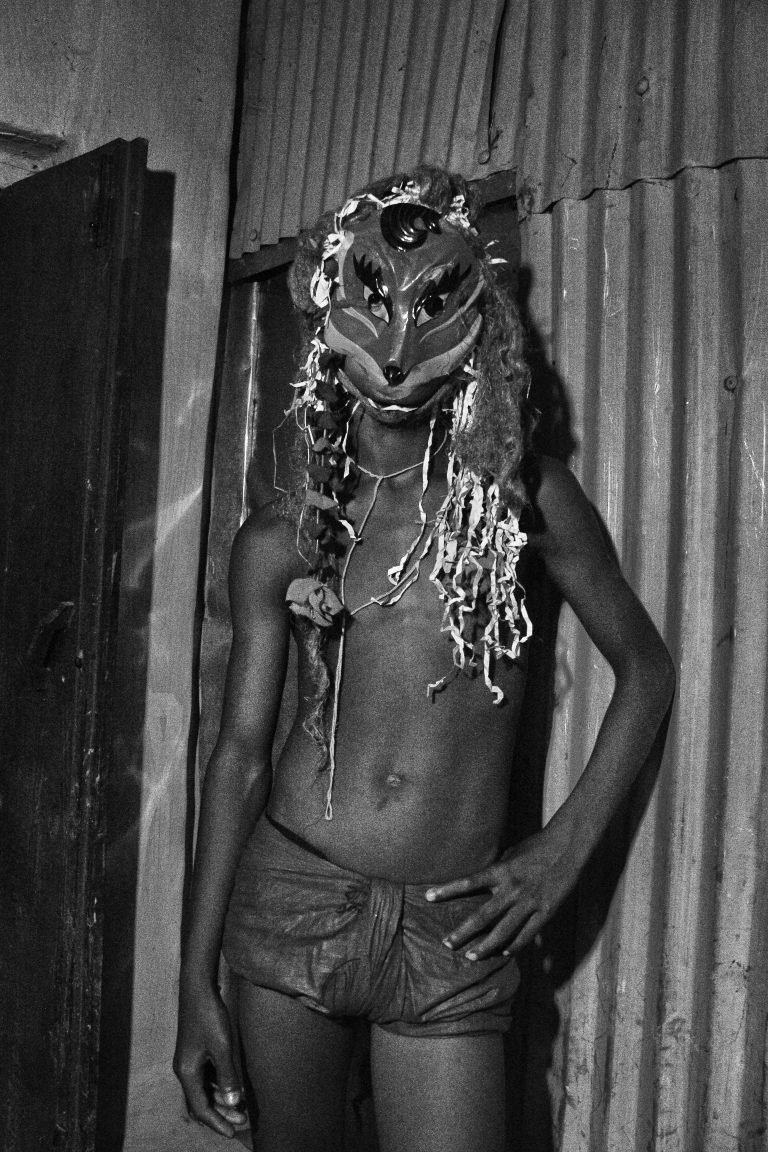

But what I got to see there in the village, were different than what I had in my visual memory! The long distance between the memory and the experiences that I had in those few days, interests me to tell the story.

Nevertheless, I was moved by experiencing the ‘other’ life that the most consumed drink of the world lives – it’s plant life that is closely connected with the land, people, culture, and the landscape that inhibits it. It is also a stimulating journey that the plant had traveled to different parts of the world for its taste and other health benefits. So, in collaboration with the Baganiya community, I started to document their everyday life and stories related to the plant following an ethnographic approach to perceive an emic perspective which is not necessarily disconnected with the garden like drinking tea or traveling for amusement.

In Bangladesh, the commercial production of tea started with the hands of the British ‘colonial’/ ‘imperial’ enterprise around the early Nineteenth century. The process was initiated during the 19th century after subsequent incidents of the industrial revolution (1760 – 1830), the invention of caffeine (1819), the First Anglo – Burmese War (1824 – 1826), the Opium Wars (1839 – 1842, 1856 – 1860), the abolishment of slavery in Britain (1865) and in Europe. Nevertheless, the conquest of Bengal through an unjust war in Plassey (1757), the Cornwallis Code that forced many people to be landless (1793), and a soldiers’ uprising in 1857 that led the Empire to take over India from the British East India Company; also played a coercive role in the Tea trade.

In Bangladesh, the commercial production of tea started with the hands of the British ‘colonial’/ ‘imperial’ enterprise around the early Nineteenth century. The process was initiated during the 19th century after subsequent incidents of the industrial revolution (1760 – 1830), the invention of caffeine (1819), the First Anglo – Burmese War (1824 – 1826), the Opium Wars (1839 – 1842, 1856 – 1860), the abolishment of slavery in Britain (1865) and in Europe. Nevertheless, the conquest of Bengal through an unjust war in Plassey (1757), the Cornwallis Code that forced many people to be landless (1793), and a soldiers’ uprising in 1857 that led the Empire to take over India from the British East India Company; also played a coercive role in the Tea trade.

Mass migration of labor and social division were among the key factors to introduce an ‘enclave economy’ within the tea estates, which still exist in the post-colonial years. British management system, credit and auction facilities in the pre- and post-production period, estate rules along with its rituals, and a quasi-trade union which best serves the owners: all persist in 163 tea gardens in Bangladesh which employs approximately a million permanent, contractual and seasonal labors among whom the majority are women – a perfect set up for ‘commodity fetishism’ which also reflected through the commercial advertisement of tea. Originally the workers in Bangladesh and their communities were brought from Bihar, Madras, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and other places of present day India (Bengal and all these places were part of British India), who were landless and living a marginal life because of the British Land Reform policy of 1793. Arkathis (Middleman) employed by the tea planters (both local and European) went to those villages and deceived these communities to work in the tea plantations where they ‘will get gold if you shake the trees’. This indentured system of labor recruitment, which still entangles Baganiyas with the garden and keeps no strings attached to the outer world, was operational from the 1840s to 1930s. But they never got to see the gold, rather received a life full of misery. Almost half of them could not make it to the plantations, as the tough journey which includes walking, boat, or rail transportation along with inhuman treatment by the organizers made the number shrink down to the fittest of the workers.

Now, there are approximately 90 different ethnic minorities that form the community, who are disconnected from their ancestral land. Unlike Bengali Muslims, who form the majority within the country, Baganiyas are mostly schedule caste Hindus with a fraction of Christianity, Islam, and other indigenous beliefs. This large diversity of ethnicity and religious beliefs were manipulated by the planters (people from different beliefs and social status forced to live together and share the scarce resources offered), another classic example of divide and rule policy implemented in the ‘Estate within the State’. The workers traveled thousands of miles with their traditional knowledge of farming, religion, culture, and so on. Afterward, these people were made to clean the jungles, hilly slopes, or abandoned plains to establish the tea estates, which comprises tea plantations, factories, nurseries, villages, bungalows, and fallow lands. Now the beautiful lush green fields that people get to see from the railroads or the highways are the landscape that these workers had worked on over the years. The tea companies brought the migrant workers, administer them into the new land, teach them to grow tea but the adaptation to the new environment was solely done by the Baganiyas. Thus, by changing the social environment of the area both the planters and the Baganiyas formed a new social relationship between humans and nonhumans of the region.

With 120 Taka a day (Just over a Euro) and other marginal benefits, a permanent worker in grade A gardens, has the most ‘secured’ life according to the law. Even the wage of the workers is largely dependent on the quality and quantity of production, as that denotes the permanent workers in grade B, and C gardens, get less than that of grade A. But that’s not the end of the story where poor access to accommodation, education, healthcare and sanitation system, safety at work, gender discrimination, child labor, and most of all, extremely low wages ‐ all these exploitations complement a theoretical framework that is widely known as ‘monoculture plantation’ that produces the most consumed drink of the world by the cheapest labors in the global economy. Hence the ‘aura’ of the centuries-old feudal structure is still evident in the ‘garden’ as a form of master and slave relation.

Even after all these, tea estates are considered gardens, that have a profound connection with the notions of paradise and civilization both in Indo-Persian and European traditions.! Eventually, the modification of the landscape of the region was done in a way, so that, the local biodiversity was completely devastated to establish the ‘imaginary garden’ as exotic land filled with exotic plants with the serene scenic beauty; entails non – western imagery in Western cosmology. The western intervention in the local ecology to establish the garden to produce the great taste as a fetishized commodity where the racialized practice of body shows the gendered landscape as a feminized representation of colony by the empire. Moreover, the alteration of the existing landscape was a justification of what they portrayed as a journey to ‘development’.

Now, Cha Chakra: Tea Tales of Bangladesh is a long-term documentary photography research project that tells the story of an imperial taste, a civilizing tool, and the most popular drink in the world, tea, which also has a social life like any other commodity or even as a plant. Cha Chakra has been conducting interviews, and collecting oral histories, old photographs, and different archival materials not only from the workers but also from different museums, and archives worldwide.